The machinery of quantum mechanics has a flavor of linear algebra and analysis. For example, quantum states exist within a Hibert space, and the Bloch sphere used to demonstrate a state of a 1-qubit system is a geometric object living in \(\mathbb R^3\). We wish to apply the abstract, continuous machinery in a discrete setting. The state labels are nonnegative integers, and measurement collapses abstract states into pure states. In this post, we study a number theoretic application of quantum mechanics.

A periodic state is a superposition of orthogonal states that have an arithmetic progression of their state labels.

Definition. Let \(r, m, b \in \mathbb N\) be the period, repetition and shift. The three integers define a periodic state as follows.

\[|\phi_{r, b} \rangle := \frac 1{\sqrt m} \sum_{z = 0}^{m – 1} |zr + b \oplus 0\rangle\]

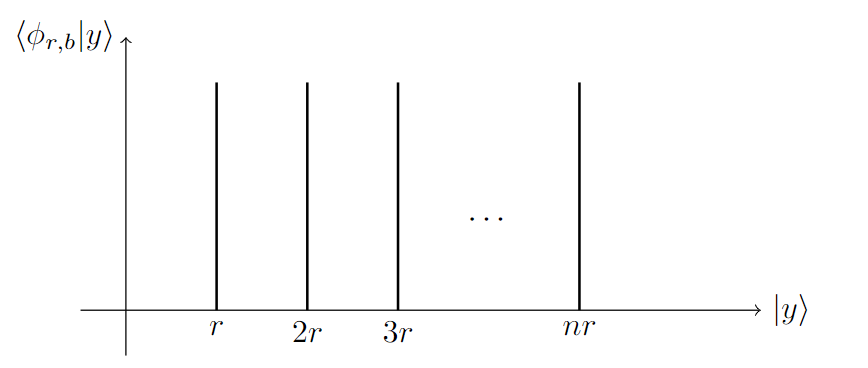

The \(\oplus 0\) signifies that the state labels are adjusted modulo \(mr\), and we omit this for simplicity for our calculations below. It is implied that the combined system has \(mr\) orthonormal states. Plotting out the amplitude with respect to state label, the periodic state can be considered as a collection of fringes that spike at a period of \(r\).

Figure. Plot of Probability amplitudes of a periodic state.

Proposition. \[QFT^{-1}_{mr}|\phi_{r, b}\rangle \ = \ \frac{1}{\sqrt r} \sum_{k = 0}^{r – 1} \exp(-2\pi i bk/r) |mk\rangle\]

proof. Expand the inverse QFT as a sum and swap the order of the double sum. Notice that the new inner sum is nonvanishing if and only if \(m|y\). This can be justified by geometry in the complex plane or by the geometric series formula.

\begin{align} QFT^{-1}_{mr}|\phi_{r, b}\rangle & = \ \frac 1 {\sqrt m} \sum_{z = 0}^ {m – 1} \sum_{y = 0}^{mr – 1} \frac 1{\sqrt{mr}} \exp(-2\pi i \frac{y(zr + b)}{mr})|y\rangle \\ & = \ \frac 1 {\sqrt m} \sum_{y = 0}^{mr – 1} \sum_{z = 0}^ {m – 1} \frac 1{\sqrt{mr}} \exp(-2\pi i \frac{y}{m}z – 2\pi i \frac {yb}{mr})|y\rangle \\ & = \ \frac 1 {\sqrt r}\sum_{y’ = 0}^{y’ = r} \exp(-2\pi i \frac {y’b} r)|my’\rangle \end{align}

On the last step, we replaced \(y \rightarrow my’\) and disposed the first summand of the phase which correspond to complete rotations. Relabel \(y’\) to \(k\) which concludes the proof. □

The proposition shows that the inverse QFT can switch the repetition and the period of a phase.

A natural question to ask is to find the period \(r\) from a given periodic state \(|\phi_{r, b}\rangle\), knowing the dimension of the system \(mr\). Measuring the output of a periodic state after processing it through an inverse QFT circuit in the computational basis yields an integer multiple of the repetition, namely \(mk\) for some \(0 \leq k < r\). If \(r\) is prime, then we can retrieve \(m = \gcd(mr, mk)\) and compute \(r = mr / r\). Even if this is not the case, simplifying the fraction \(mk/mr\) and taking the denominator will yield integer \(r\) by a good probability.

Let \(r’\) be the denominator of the simplified fraction \(mk/mr\) where \(mk\) is obtained by the process above. It must always be the case that \(r’|r\). If, by some method one can test \(r|r’\) we can repeat the entire process until \(r’\) satisfies the condition and conclude \(r = r’\).

We continue to discuss the algorithm that can test if the purported phase \(r’\) is indeed the period.

Problem. (Phase Testing). Given an integer \(r’\) and a state \(\phi_{r, b}\), find a quantum circuit that determines \(r|r’\).

Suppose we have a shifting gate \(X_{r’}\) such that

\[X_{r’} |n\rangle \ = \ |n + r’ \rangle. \]

It is straightforward to verify that the period state and the shifted periodic state are orthogonal if and only if \(r|r’\). More precisely,

\[ \langle\phi_{r, b}| X_{r’}|\phi_{r, b}\rangle \ = \begin{cases} 0 (\text{if} \hspace{3mm} r|r’)\\ 1 (\text{otherwise}) \end{cases} \]

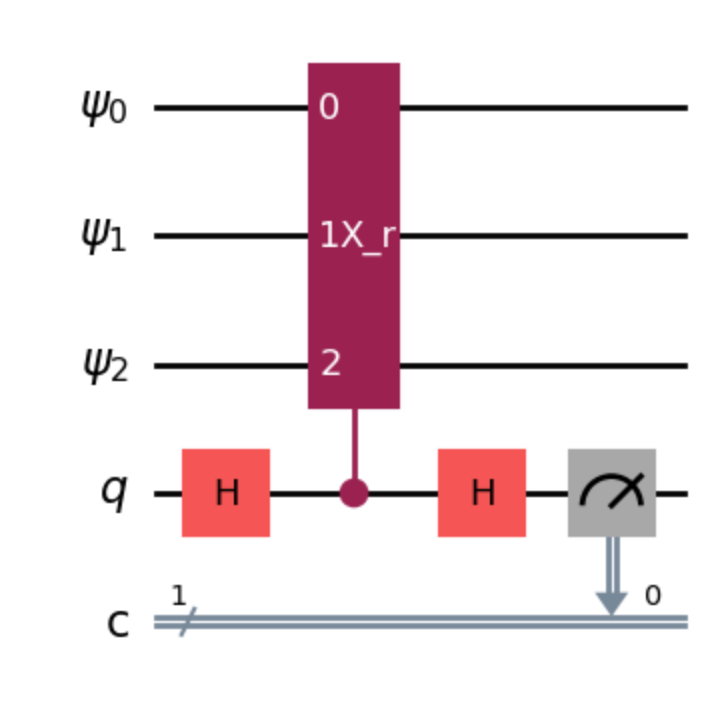

In other words, \(|\phi_{r, b}\rangle\) is an eigenstate of the shifting gate with eigenvalues \(0\) or \(1\) depending on the condition \(r|r’\). Using the idea of phase kickback, we present the following quantum gate.

Figure. A solution for Period Testing .

If the periodic state is passed through the \(|\psi\rangle\) channels and \(|0\rangle\) through the ancilla channel \(q\), the circuit always measures \(|0\rangle\) if \(r|r’\). Otherwise, the circuit measures \(|0 \rangle\) by a probability of \(1/2\).

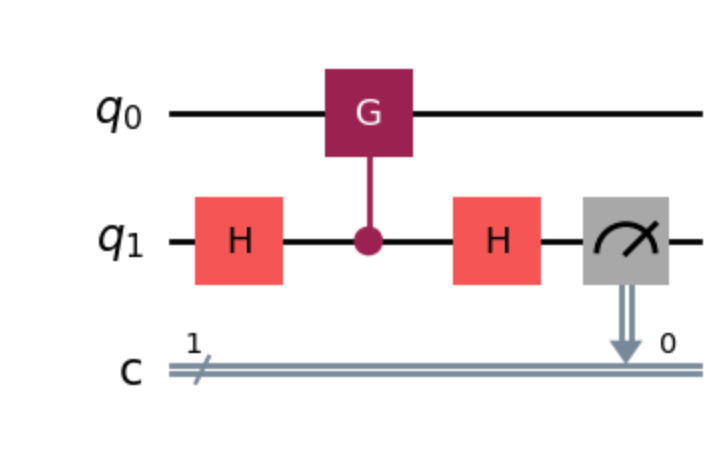

We end the post with a nifty physicist technique to compute the ancilla qubit probability amplitudes. Consider a circuit that employs the Hadamard trick for phase kickback.

Figure. Hadamard trick on a two qubit system.

Let \(q_0 = |\psi\rangle\) and \(q_1 = |0\rangle\) be the input of the circuit. Before evaluation, the state is

\[ \frac{|\psi\rangle + G|\psi\rangle} 2|0\rangle + \frac{|\psi\rangle – G|\psi\rangle} 2 |1\rangle.\]

Technically, the product between the two states are tensor products. But we claim that a probability amplitude can be a vector in Hilbert Space. The probability of measuring the ancillary qubit to state \(|0\rangle\) is therefore

\[ P_0 \ = \ \bigg\|\frac{|\psi\rangle + G|\psi\rangle}{2}\bigg\|^2 \ = \ \frac 1 2 + \frac {\Re(\langle\psi|G|\psi\rangle)} 2 \]

Substitute \(G, \psi\) with \(X_{r’}, \phi_{r, b}\). We know that the overlap integral is either \(0, 1\).

The beauty of using the Hadamard trick is that the \(\psi\) state passed in to the target qubit need not be measured to reach a probability that depends on the overlap integral. Without measuring the ancillary qubits after two Hadamard gates, one must construct a gate that emulates the unknown state from a pure state which might not be possible in certain cases. The two hadamard gates acting on the ancilla qubit superposes the system such that the overlap shows up in the process of computing the probability amplitude.

Leave a Reply