We have learned that applying the Hadamard gate to multiple input terminals allow quantum computers to handle multiple classical cases in one run. A classical example that demonstrates the use of this technique is the Deusch-Joza algorithm. Assuming that the oracle function is either constant or balanced, the algorithm allows Alice to deduce the type of the function by one iteration over the quantum circuit.

In this article, we consider more uses of the Hadamard superposition. Also, recall that controlled gates allow a phase kickback into the control qubit if the target qubit is in an eigenstate.

Problem (Bernstein-Vazirani)

Given a binary string \(a \in \{0, 1\}^n\), a quantum oracle maps \(n + 1\) dimensional quantum state to itself as follows. \[ |x\rangle|k\rangle \mapsto |x\rangle |k \oplus x \cdot a\rangle \] Find a quantum circuit that computes \(a\) in a single trial.

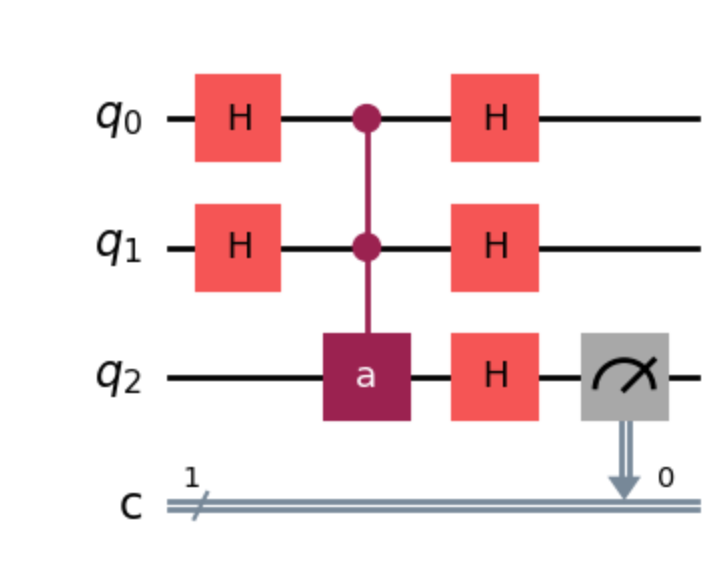

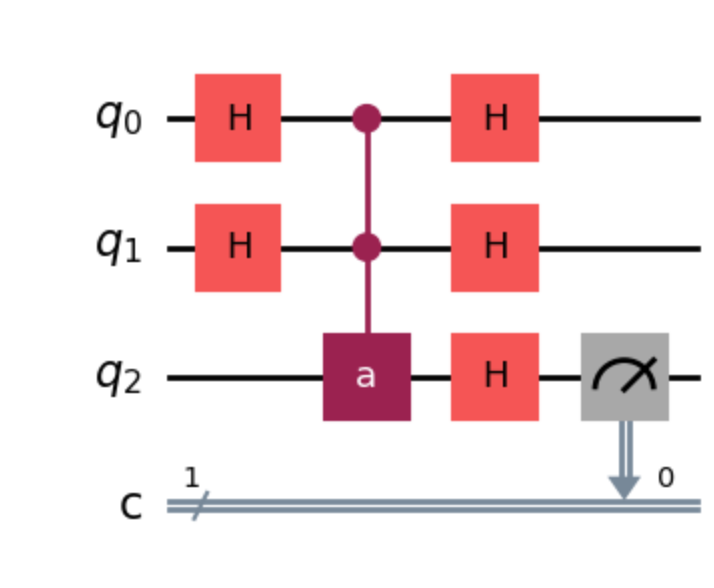

Instead of listing out the general solution and proof, we demonstrate the solution for the n=2 case. Fix the binary string as (a = 01). Since the Hadamard gate is a self inverse of itself, our hope is that stacking two layers of Hadamard between the oracle evaluation \(a\) will do the trick. By trial and error, we deduce the following quantum circuit.

Assume that the input in all registers are fixed to be zero. Compute the state of the circuit before applying the Hadamard gate and the measurement on register 2. Though the second layer of Hadamard are applied in the same period, we separate the last gate applied in the second register. It is straightforward to verify the cancellation of all other states other than \(|00\rangle, |a\rangle\) for the first repository leads to the state

\[ \frac 1 2 \left( |00\rangle + |a\rangle \right) |0\rangle + \frac 1 2 \left( |00\rangle – |a \rangle \right) |1\rangle \]

Apply the Hadamard Gate to the third repository. The final state before the measurement is \[ \frac 1 {\sqrt 2} \left( |00\rangle |0 \rangle + |a \rangle | 1 \rangle \right) \] and the measurement on the third repository to \(|1\rangle \) removes the first summand. This argument can be easily generalized to an \(n+1\)-qubit system. The crux of the proof is to justify the following equality. \[ \sum_{j = 0}^{m – 1}\sum_{k = 0}^{m – 1} \frac 1 {m} (-1)^{j \cdot k}|j\rangle |0 \oplus k \cdot a\rangle \ = \ |00\cdots 0\rangle \left( \frac 1 2 |0\rangle + \frac 1 2 |1\rangle \right) + |a\rangle \left( \frac 1 2 |0\rangle – \frac 1 2 |1\rangle \right) \]

Fix a state \(j\) and consider the balance of the signs. Notice that the only case where the terms are nonvanishing is when \(j = 0\) and all signs are positive or \(j = a\) so all the signs of \(|0 \oplus k \cdot a\rangle\) are unified for a fixed \(j\). In all other cases, signs of the terms are balanced, which justifies the equality.

Problem (Phase Estimation)

Suppose an \(n\)-dimensional quantum system is given by \[ \frac 1 {\sqrt{m}} \sum_{y = 0}^{m – 1} \exp(2\pi i \omega y )|y\rangle \] Find a quantum circuit that estimates the phase parameter \(\omega \in \mathbb R\) in a single trial. (\(m = 2^n\))

We simplify the combined state as a tensor product of 1-qubit states.

\[ \frac 1 {\sqrt m} \sum_{y = 0}^{m – 1} \exp(2 \pi i \omega y) |y \rangle \ = \ \prod_{k = 0}^{m – 1} \frac 1 {\sqrt 2} \left( |0\rangle + \exp(2\pi i \cdot 2^k \omega \right)|1\rangle \]

Justify this equation by expanding the right-hand side.

Once this equality is justified, we proceed with retrieving the binary representation of \(\omega\) in reverse order. Recognize that the integer part of (\2^k \omega)\ results in a full rotation and hence can be ignored. By applying an Hadamard gate to the first qubit we retrieve the last binary digit of \(\omega\).

\[\frac 1 {\sqrt 2} |0\rangle + \exp (2\pi i \cdot 0.\omega_n)|1\rangle = \frac 1 {\sqrt 2} |0\rangle + \frac 1 {\sqrt 2}(-1)^{\omega_n} |1\rangle \ \mapsto |\omega_n\rangle\]

To retrieve the other indices of \(\omega\), apply controlled rotations to kill off the phases incurred by the lower digits.

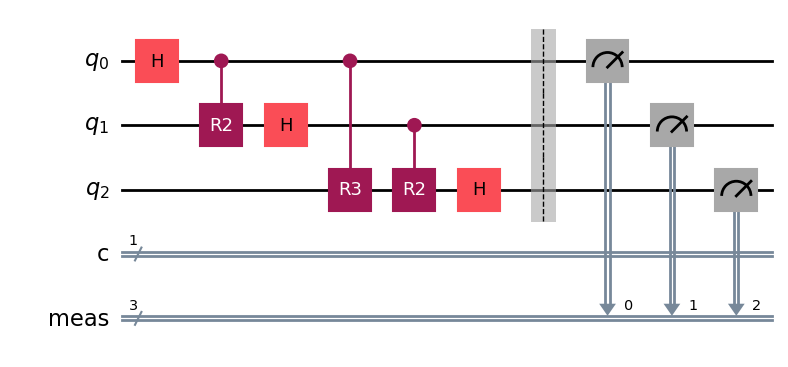

The following circuit solves the phase estimation problem for \(n = 3\). The RN gates refer to z-directional rotations by an angle \(2\pi i \frac 1 {2^N}\).

In our crude survey, we implicitly assumed that \(\omega\) is an integer multiple of \(\frac 1 {2^n}\). Even when this condition is violated, the algorithm yields an approximation of \(\omega\) by a probability greater than \(\frac 8 {\pi^2}\), where the range of uncertainty is between the two closest integer multiples of \(\frac 1 {2^n}\).

Leave a Reply