In this post, I wish to introduce two elementary number theory problems and their solutions. The solutions require no mathematical prerequisites other than basic understanding of logic and integer valued functions. The typical structure of these problems are as follows. A functional equation is given, along with the domain and the range of the function. We are asked to find all the solutions for the equations, i.e. all functions that satisfy the conditions.

As a rule of thumb, the strategy is to guess a simple solution and somehow justify that there are no other solutions. Looking at specific evaluations at certain points might be helpful. A firm conviction for your own solution set will allow the proof writer to not be veered away to the forest of meaningless algebra.

The problems are from the book Putnam and Beyond: Gelca, Razvan: 9780387257655: Amazon.com: Books

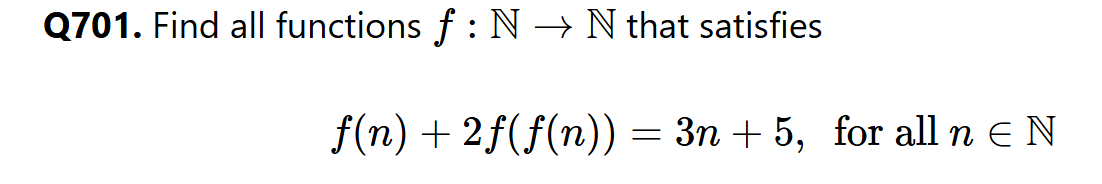

Q701. Find all functions \(f:\mathbb N \rightarrow \mathbb N\) that satisfies

\[f(n) + 2f(f(n)) = 3n + 5 , \hspace{3mm}\text{for all } n \in \mathbb N\]

Before we list out the solution, stick to the strategy. Try out easy linear functions that satisfies the equation. The successor function \(f(n) = n + 1\) satisfies the equation. If there existed a complicated solution, life would have been harder. We hope for the best and attempt to show that the successor function is the unique solution. Note that the range of \(f\) is over nonnegative integers, hence greater than zero.

Solution. Let \(n = 0\) and we deduce

\[f(0) + 2f(f(0)) = 5\]

Since \(f(0), f(f(0))\) are both nonnegative integers, \(f(0)\) must either be \(1, 3\). If \(f(0) = 3\), then \(f(f(0)) = f(3) = 1\). But then, \(f(3) + 2 f(f(3)) = 14\) so \(f(f(3)) = 13/2\), which is a contradiction. Therefore, \(f(0) = 1\). Moreover, we show that \(f(n) = n + 1\) implies \(f(n + 1) = n + 2\). From the given functional equation, plug in \(n\).

\[f(n) + 2f(f(n)) = n + 1 + 2f(n + 1) = 3n + 5\]

Equating the final two terms yield the desired result. □

Q702. Find all functions \(f:\mathbb Z \rightarrow \mathbb Z\) such that

\[2 f(f(x)) – 3 f(x) + x = 0, \hspace{3mm} \text{for all }x \in \mathbb Z\]

The identity function solves the equation. Other solutions will give us a headache. So we wish to prove that \(f(x) = x\) for all \(x \in \mathbb Z\). We define \(g(x) := f(x) – x\) and show that \(g(x) = 0\) identically. If subtracting won’t work, then we can attempt division, i.e. set \(h(x) = f(x) / x\) and show \(h(x) = 1\) identically.

Solution. The introduction of \(g(x)\) simplifies the equation as

\[2 g \circ f(x) – g(x) = 0 \]

and by induction, one can show, for any nonnegative integer \(j\),

\[g(x) = 2^j g\circ f^{(j)}(x)\]

which implies that \(2^j|g(x)\) for arbitrarily large \(j\). It must be the case that \(g(x) = 0\). □

As mentioned in the beginning of the post, having an idea of the solution is important. From the motivation, one can try to verify the idea partially as we did in the first problem to show that \(f(0) = 1\). Or, one can try to come up with an auxiliary function like \(g(x) = f(x) – x\) for the second problem. The remaining work is to look keenly for specific conditions.

Leave a Reply